Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are now part of the common investor’s toolkit, and accounting for more than USD 11 trillion Asset Under Management (AUM) globally. Despite their (growing) popularity, some investors are still unclear about the way they work, trading them (or not) based on misconceptions.

This article focuses on the basic principles underlying ETFs creation, redemption and trading, and is a summary of a much more comprehensive and highly recommended read, published by the CFA Research Foundation:

A Comprehensive Guide To ETFs (2nd edition) | Module 1: ETF Features and Evolving Landscape, CFA Institute Research Foundation, 2025

The full article is freely available here: https://rpc.cfainstitute.org/sites/default/files/docs/research-reports/hill_rf_brief_2025_etfs-evolving_module-1_2ed_online.pdf

What is an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF)?

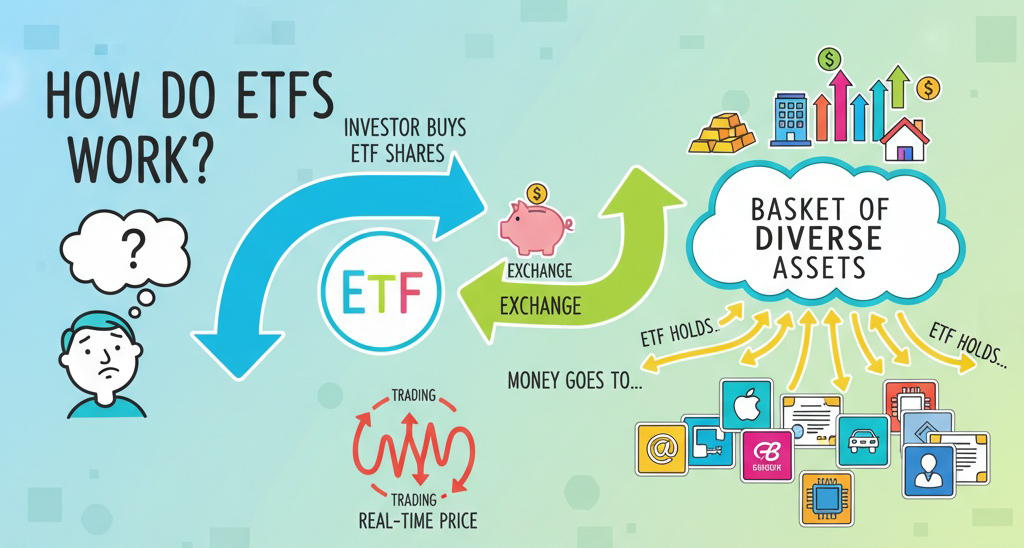

An ETF is a type of investment fund that holds a basket of underlying assets—such as stocks, bonds, or commodities—and is traded on stock exchanges.

ETFs creation, redemption and trading

ETFs present features similar to stocks, as they are listed and traded in a stock exchange, and to mutual funds, as they usually offer exposure to a diversified basket of securities.

However:

- unlike listed stocks, their shares/units do not follow the typical listing process via an Initial Public Offering (IPO);

- unlike mutual funds, they are not available to investors via a direct subscription/redemption process through an asset manager (so when you buy or sell shares of an ETF, the asset manager is not aware of your orders submitted via the stock exchange).

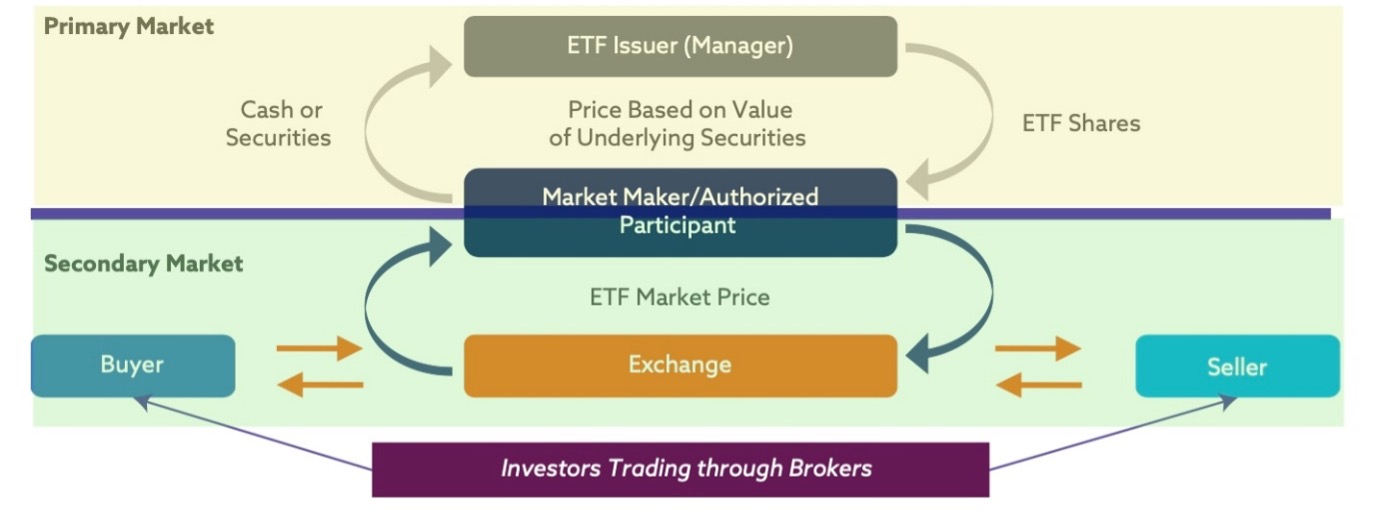

For ETFs, it is important to distinguish between the primary (non-listed) market and the secondary (listed) market, as illustrated in the following illustration.

ETF Creation, Redemption, and Trading Process

Source: A Comprehensive Guide To ETFs (2nd edition) | Module 1: ETF Features and Evolving Landscape, CFA Institute Research Foundation, 2025

- Primary market: this is the “behind the scenes market”, where ETF shares are created and redeemed. This part of the market is for selected operators only: the asset manager (ETF issuer) and the Authorised Participant (AP).

The APs (large broker/dealers, often market makers) deal directly with the ETF issuer, asking for the creation or the destruction of ETF units, in exchange for cash or, more commonly, a selected basket of securities (generally matching the ETF’s full composition). - Secondary market: this is where investors can buy or sell units of ETFs, listed in the securities exchange, via a brokerage account (offered, for example, by a bank). Very often, when investors buy or sell ETF units, nothing happens at the fund manager’s end: the listed units are simply changing ownership, from investor A to investor B.

The question then is: how can an ETF’s asset under management grow or shrink, based on the excess of demand or offer of its shares in the market, during a given trading day?

The answer lies in the primary market, where the APs – able to also trade in the secondary market as market makers – play an important role in keeping the value of the ETF units aligned with the values of its underlying securities.

The APs have an economical incentive to do so, as this represents for them an arbitrage opportunity, with the possibility of making profits without risk. Despite being driven by their own profit opportunities, APs create a mechanism that brings efficiencies to the market, benefiting investors.

Each day, ETF issuers (like asset managers) publish a list of securities — known as the “creation basket” — that they want to add to or remove from the fund (this also adds transparency for investors, who can monitor the fund manager’s activities on a daily basis).

APs can buy from the ETF issuer newly created ETF units, in exchange for listed shares listed for the same amount and proportion dictated by the “creation basket”. The APs usually trade stocks they hold in their account, or they can get them separately. For ETF shares, the standard transaction is typically in large blocks called “creation units” (usually 50,000 shares).

Rarely, the APs could trade cash in exchange for ETF’s units but this process is less efficient as the ETF issuers would then have to convert the cash into the securities required by the portfolio they are managing, charging a fee to the APs. Whenever possible, APs prefer in-kind exchange, using a basket of securities instead of cash.

When new ETF shares are created, APs sell these shares in the secondary market to investors, supporting ETF supply and market liquidity. If APs wish to liquidate ETF shares, they present a block of ETF shares to the ETF issuer and receive the equivalent basket of underlying securities, which they can then keep, or sell.

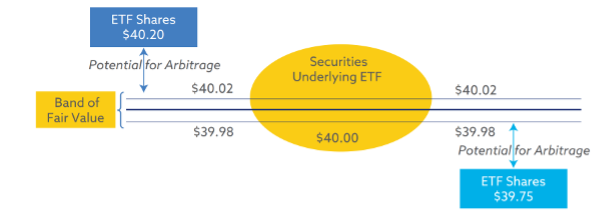

Arbitrage opportunity: when ETF shares trade above their intrinsic value (due to high demand of ETF’s shares), APs sell ETF shares, receiving (i.e. buying) the underlying securities. This put downward pressure on the ETF price, and upward pressure on the underlying securities, restoring price equilibrium. When there is an excess of demand for ETF shares, the APs will ultimately ask the ETF issuer to create more ETF shares, delivering the underlying securities (and increasing the ETF’s asset under management).

The inverse mechanism applies when ETF shares trade below their intrinsic value.

Example: APs intervene if the ETF price diverges significantly from its underlying securities, profiting from the “arbitrage gap”. For example, if ETF shares are selling for $40.20 but their fair value is $40.00, APs buy the underlying stocks and exchange them for ETF shares, then sell those ETF shares at the higher price, pocketing the difference. This activity pushes the ETF price down and the underlying stock prices up, quickly neutralizing any inconsistencies.

The narrow arbitrage band around fair value varies by ETF and is typically smallest for funds with the most liquid underlying securities. The costs and risks of arbitrage, including trading fees and minimum creation unit sizes (which are set by the ETF issuer), influence when APs step in to create or redeem.

The ETF Arbitrage Band and Process

Source: A Comprehensive Guide To ETFs (2nd edition) | Module 1: ETF Features and Evolving Landscape, CFA Institute Research Foundation, 2025

Note: the APs absorb all the costs of acquiring new securities for the ETF, which is a significant advantage of handling flows into and out of the fund. Investors pay only when buying or selling their ETF shares, and these costs are reflected in the ETF trading spread.

Current ETF shareholders are thus shielded from the negative impact of transaction costs from money entering and exiting a fund from new or redeeming shareholders. This is a distinct advantage from traditional mutual funds, where new or redeeming investors’ costs can be shared amongst all fund-holders.

As the ETF market becomes more competitive, APs will prefer ETF issuers that apply more favourable economic conditions for the creation/redemption of ETF units, maximising the APs’ arbitrage profits. For ETFs tracking the same securities baskets, investors will prefer to trade ETFs with lower bid-ask spread, pushing ETF issuers (asset managers) to lower management fees to be more competitive.

Note: index-tracking ETFs (giving exposure to passive management) tend to be the most popular choice, as the underlying securities they track are usually very liquid and can be easily traded by the APs. It is however possible for the ETF issuer to choose a different basket of securities to track in lieu of an index, providing exposure to actively managed investments (that, by definition, try to beat an underlying index). If the active manager is including smaller, less liquid stocks in the creation basket, the trading spread of the ETF’s shares will likely rise (i.e. a higher price discrepancy will be required by the AP before entering the market).

It is very important for investors to understand what an ETF is tracking, before making an investment.

Further themes to be explored

If it is clear how ETFs work, it is possible to delve more into the details, as outlined by the paper published by the CFA Institute Research Foundation.

For the most curious, these are some of the themes approached in the paper: ETF shorting; why ETF tracking multi-country indices tend to be more expensive; ETN (Exchange Traded Notes) vs ETF; possible tax efficiencies offered by ETFs; ETF clearing process.